Abstract

This research paper explores the intricate world of rammed earth, a building technique deeply rooted in history and currently experiencing a resurgence as a sustainable and visually appealing construction material. By compacting a mixture of soil elements, including sand, gravel, and clay, and occasionally incorporating stabilizing additives like cement or lime, rammed earth offers durable wall structures.

The paper delves into the historical background, advantages, challenges, and prospects of rammed earth in the construction industry. Two significant case studies are presented to exemplify the contemporary application of this ancient method. The first case is the Terra Centre in Southwest China, a model of sustainable rural development. This project follows a philosophy of utilizing local materials, technology, and labor, successfully integrating traditional rammed earth techniques. Design elements such as double-glazed windows, insulated roofs, and a bamboo structure enhance thermal efficiency, making a substantial impact on environmental, economic, and social sustainability in rural areas.

The second case study is the Nk’Mip Desert Cultural Centre in Osoyoos, British Columbia, Canada. Conceived by Hotson Bakker Boniface Haden architects, this award-winning facility embodies modern rammed earth construction. Its walls, reaching up to 80 cm thick, provide significant thermal mass, playing a crucial role in the building’s energy efficiency.

In conclusion, the paper juxtaposes traditional and contemporary methods of rammed earth construction, tracing its evolution from a fundamental building resource to a sophisticated construction material. This comparison encompasses various aspects such as material composition, formwork techniques, compaction methods, wall dimensions, moisture management, insulation, strength, design flexibility, sustainability, cost-effectiveness, quality control, and compliance with building codes and regulations.

Introduction

Rammed earth is a building technique that creates long-lasting and sustainable walls using compacted soil, frequently a mixture of sand, gravel, and clay cemented with additions like cement or lime. (Soriano et al. 2012).Over the course of architectural history, building materials and techniques have undergone constant evolution in response to changing climatic conditions as well as human preferences. Rammed earth is one such material that is surprisingly relevant in the present day. This technology, which is based on the straightforward process of compacting raw earth into solid forms, not only provides strength and durability but also serves as an example of sustainable construction.

Although rammed earth has a long history, it has seen a renaissance recently, moving beyond its conventional uses and combining with cutting-edge methods and tools. In the current era, as environmental concerns increasingly challenge our planet and the construction sector seeks sustainable practices, rammed earth construction presents an ecologically sound option that does not compromise on aesthetics or functionality.

The fascinating history of rammed earth is explored in this study, along with its developmental path, beginnings, and current advances that put it at the forefront of an applied construction. By means of an extensive investigation, the goal of this paper is to reveal the incremental improvements that have taken rammed earth from primitive building materials to advanced construction material. This paper will also investigate the possible challenges and limitations this material may present for the building industry in the future

History

Rammed earth, also known as pisé de terre, has a rich history spanning over ten millennia. While the earliest documentation of this construction technique in Western Civilization is credited to the Roman Pliny the Elder around 79 AD, indications of its application have been discovered in China (around 5000 BCE), (Jaquin 2011) Europe, and various other regions predating his era with each region adapting and refining the method to suit local climates and materials. In the Great Wall of China, the oldest and most iconic example of rammed earth construction, one witnesses the enduring strength and resilience of this building method.

As civilizations evolved, so did the use of rammed earth. In the Middle East, particularly in ancient Mesopotamia, ziggurats—massive, stepped structures—were constructed using a form of rammed earth. The method continued to thrive during the Roman Empire, with examples like Hadrian’s Wall in Britain showcasing the versatility of rammed earth in various terrains.

Its popularity, however, waned with the advent of modern construction materials and techniques. The efficiency and speed of industrialized construction methods overshadowed the labor-intensive process of rammed earth construction. Additionally, evolving architectural trends and the desire for modern aesthetics contributed to the fading popularity of this traditional building technique.(Jaquin 2011).Despite its decline, the legacy of Rammed Earth endures, serving as a testament to the ingenuity of past civilizations in their pursuit of sustainable and enduring architectural solutions.

Rammed earth has gained popularity again in recent years as an environmentally responsible and sustainable building material. Growing awareness of the effects modern construction methods have on the environment is the driving force for this comeback. Rammed earth’s thermal mass properties, providing natural insulation, contribute to its appeal in the context of sustainable architecture. Modern architects and builders are exploring innovative ways to incorporate rammed earth into contemporary designs, blending ancient wisdom with modern technology.(Losini et al. 2023)

In regions prone to earthquakes, such as parts of South America and Asia, rammed earth has regained favor for its seismic resistance, a quality inherently present in its dense composition.

3. Literature Case Studies

3.1 Project Introduction (The Terra Centre )

The Terra Centre in Southwest China is a pioneering project that exemplifies an innovative approach to sustainable rural development. The initiative, led by the One University One Village (1U1V) team, focuses on the use of traditional rammed earth construction techniques combined with a “local material, local technology, local labor” principle to improve the safety, quality, and dignity of the living environment without substantially increasing environmental load. The Terra Centre, built in Kunming, serves as a working base for researching, promoting, training, and transferring knowledge about this construction approach. It has significantly contributed to the long-term environmental, economic, and social sustainable development of poor rural areas, responding to multiple targets of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)(Wan et al. 2022).

Figure 1. Terra Centre (Arch Daily. May 27, 2021)

The project provided a comfortable and artistic building environment for various users, including teachers, students, scholars, and villagers. It created high architectural quality and aesthetics, despite being built by village craftsmen rather than a professional construction team. The building’s design incorporates double-glazed windows, insulated roofs, and a bamboo roof structure to improve its thermal performance. Additionally, the project’s passive design, based on the local climate conditions of Kunming, aims to reduce the environmental load of the building and reflect the regional characteristics. The use of local and natural materials, such as abandoned soil from the excavation of a high-rise building foundation 6 km away from the project site, minimized the embodied energy and responded to the sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources.

3.2 Environmental Sustainability

3.2.1. Passive Design

The design of the Terra Centre in Kunming is thoughtfully aligned with the local climate, aiming to reduce environmental impact and highlight regional characteristics. Kunming’s mild, humid subtropical climate, characterized by dry winters and mild summers with significant day-night temperature variations, influenced the architectural approach. (Wan et al. 2022).

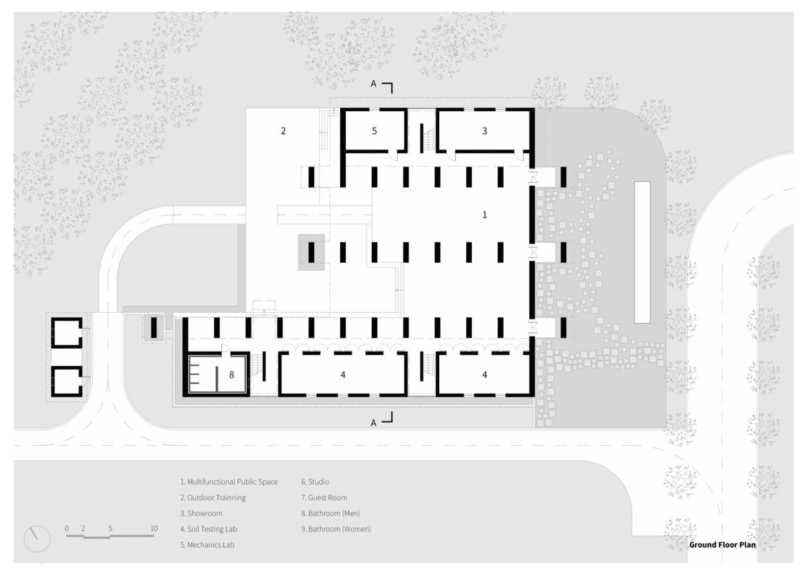

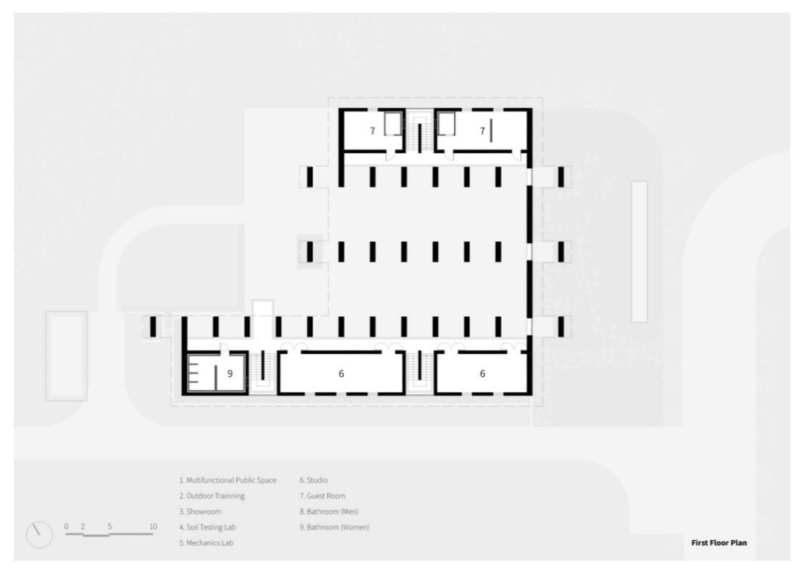

Figure 2. Ground floor plan of Terra Centre (Wan et al. 2022)

Figure 3. First floor plan of Terra Centre (Wan et al. 2022)

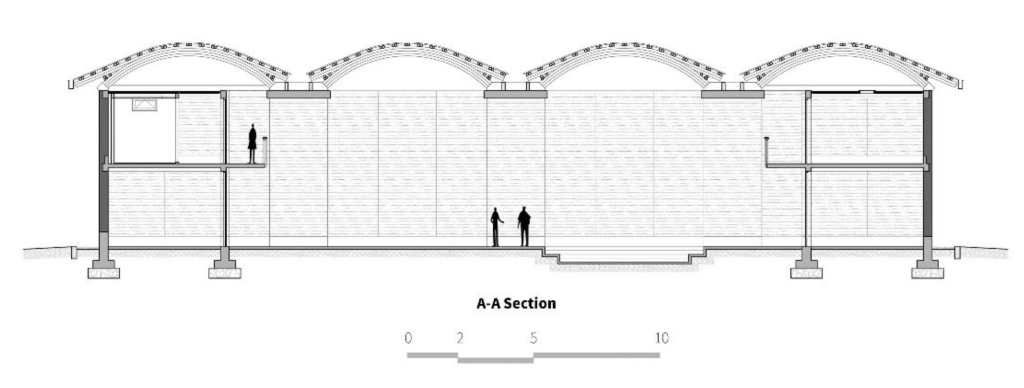

The center features a semi-outdoor space with top lighting for passive solar heating in winter and natural ventilation in summer, enhancing comfort for various activities. Functional spaces like labs and studios are strategically placed on either side of the building, with the main rooms facing southwest and utilizing floor-to-ceiling windows for optimal natural light (figure 2, figure 3, figure 5). To minimize energy use, indirect daylighting is employed, reducing the need for artificial lighting (figure 4). The building incorporates concrete columns within rammed earth walls to enhance thermal performance and avoid cold bridges, while double-glazed windows further improve insulation. The low-maintenance landscape includes a gravel and stone front yard, designed for functionality and drainage. Importantly, the construction was tailored to be straightforward, enabling local villagers to be trained and employed as craftsmen, thus aligning the project with sustainable social and economic objectives.

Figure 4. Indoor indirect sunlight of the Terra Centre (Wan et al. 2022)

Figure 5. A-A section of the Terra Centre. (Wan et al. 2022)

3.2.2. Local Building Materials

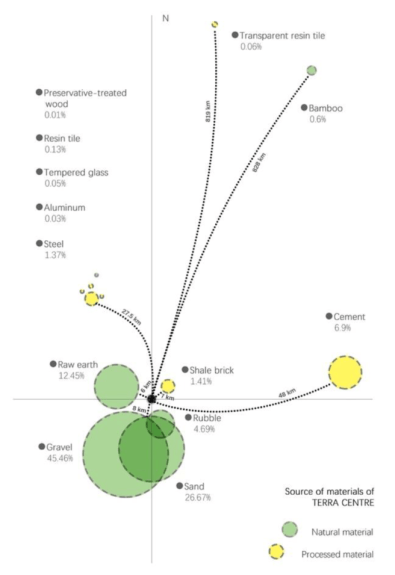

About 89% of building materials by weight were locally sourced natural materials like raw earth and bamboo, minimizing embodied energy. The walls, made without industrial stabilizers, are fully recyclable and pollution-free, while the bamboo roof offers low embodied energy. The project’s design significantly cuts down carbon emissions, potentially reducing the lifecycle carbon footprint to just 25-38% of that of conventional buildings in the region. Structural innovations like concrete tie columns and foundation ring beams enhanced seismic resilience while retaining traditional rammed earth wall construction by local laborers. The extremely low-carbon, energy-efficient building requires no active heating or cooling.

Figure 6.Source of the Terra Center’s Materials (weight percentage). (Wan et al. 2022)

3.3 Social Sustainability

To enhance the strength and seismic performance of the Terra Centre, the project team optimized soil properties by adding natural aggregates like gravel and sand, achieving a compressive strength of over 2.2 MPa for the rammed earth walls. They used air compressed rammers and lightweight aluminum alloy formwork for construction, replacing traditional wooden tools (Figure 7). The structural design includes a bearing wall system with reinforced concrete tie columns and ring beams integrated into the rammed earth walls, improving anti-shearing performance and facilitating the installation of doors and windows. These measures enhance structural integrity and seismic resistance (Figure 8). Additionally, the durability of bamboo, used for roofing, was improved through high-pressure immersion, with prefabricated standardized arch structures for reliability (Figure 9). The building, constructed primarily by local villagers, boasts high architectural quality and aesthetics, offering a comfortable environment with effective thermal performance. The design omits active cooling and heating systems, leveraging the natural thermal qualities of rammed earth and the local climate of Kunming to maintain comfortable indoor temperatures most of the year.

Figure 7. Rammed earth wall construction of the Terra Centre (Wan et al. 2022)

Figure 8. Concrete tie columns and ring beams of the Terra Centre (Wan et al. 2022)

Figure 9. Construction of bamboo roof structure of the Terra Centre. (Wan et al. 2022)

3.4 Economic Sustainability

The affordable construction cost and low operating expenses increase housing accessibility for low-income rural residents. Knowledge exchange platforms between academia, government, professionals and villagers enabled effective partnerships and policy impacts favorable for sustainable rural development. By creatively integrating local materials, labor, technology and culture with targeted scientific improvements, the Terra Centre and associated rural projects demonstrate a holistic model for enhancing environmental, social and economic sustainability in remote mountain villages (Wan et al. 2022).

3.2 Project Introduction (Nk’Mip Desert Cultural Centre)

The Nk’Mip Desert Cultural Centre in Osoyoos, British Columbia, Canada, stands as a testament to the innovative use of rammed earth as a construction material. This award-winning structure, designed by Hotson Bakker Boniface Haden architects, showcases the potential of rammed earth in modern architecture. The 1,200 square meter building is constructed primarily from rammed earth, with walls up to 80 cm thick, providing excellent thermal mass and contributing to the building’s energy efficiency(Goh et al. 2010). This feature allows the structure to maintain a stable indoor temperature, reducing the need for artificial heating and cooling. This is particularly beneficial in arid regions, where extreme temperature variations occur between day and night. The material’s ability to store and release heat gradually helps maintain a comfortable indoor environment, reducing the need for artificial heating and cooling systems.(Serrano, de Gracia, and Cabeza 2016).

Figure 1. Nk’Mip Desert Cultural Centre (Arch Daily. May 16, 2014.)

The use of rammed earth in the Nk’Mip Desert Cultural Centre offers several advantages. First and foremost, this material exemplifies sustainability, illustrating its capacity to merge traditional insights with contemporary technological innovations, thereby reflecting the center’s strong commitment to environmental stewardship.

3.3 Materials

The primary building material used in the Nk’Mip Desert Cultural Centre is rammed earth sourced from the construction site itself (Lu and Liu 2013). The walls of the facility were constructed from more than 8,100 t of raw earth composed predominantly of glacial till – a readily available local material (CMHC 2010). This choice minimized material transportation costs and associated carbon emissions while enhancing bioregional identity. The raw earth comprises a specific Particle Size Distribution (PSD) with 64% sand, 30% silt, and 6% clay, conforming to existing rammed earth construction standards. To modify the site soil to this engineered specification, sandy loam glacial till from elsewhere on the Osoyoos Indian Reserve was blended with the heavier native clay subsoil excavated for the building’s foundations. This produced an ideal rammed earth mix with excellent compaction capabilities (CMHC 2010).

A small quantity of Portland cement (less than 5% by weight) was introduced as a stabilizer to enhance the material’s compressed strength and resistance to water damage. Cement stabilization also enabled thinner wall sections compared to traditional rammed earth designs, reducing the building’s embodied energy (Kennedy 2008).

Additionally, a proprietary chemical hardener was sprayed onto the completed wall surfaces to protect the exterior façade from erosion by wind and rain. Apart from the rammed earth walls, other materials used in the Desert Cultural Centre include timber glue laminated beams, timber decking, aluminum roof membranes, exposed concrete, and insulated glazing units (Kennedy 2008). Welded wire mesh installed at 200 to 400 mm spacing was used as reinforcement in critical areas like lintels, sills and shear walls. These additional materials supplemented the thermal and structural capacity of the rammed earth while fulfilling other functional roles.

However, there are also limitations to using rammed earth. The construction process is labor-intensive and requires a high level of expertise to ensure the structural integrity and durability of the walls. The need for large formwork also increases the initial costs. Furthermore, while rammed earth is a durable material, it is susceptible to erosion if not properly protected from the elements, requiring careful design and maintenance to ensure longevity.

3.4 Technology Integration

Several technologies were thoughtfully incorporated into the Nk’Mip Desert Cultural Centre’s fabric to augment the thermal and structural capabilities of its rammed earth walls:

- High performance glazing units featuring low-emissivity coatings and inert gas fills were integrated into the thick walls, balancing visibility and insulation needs.

- Polystyrene rigid insulation inserts were sandwiched between staggered timber stud walls abutting the rammed earth, enhancing envelop insulation while minimizing thermal bridging.

- Hydronic radiant in-floor heating and heat recovery ventilation ducted through interior concrete slabs evened out heat distribution.

- Careful shading, spatial zoning and the strategic use of thermal chimneys facilitated passive ventilation and cooling.

This suite of technologies boosted the building’s energy efficiency. In conjunction with the high thermal storage capacity of dense rammed earth walls, the integrative passive heating, cooling and ventilation strategy significantly reduced mechanical system demands (CMHC 2010)

Comparison of Traditional and Modern Technique (ChatGPT, 2023)

| Aspect | Traditional Technique | Modern Technique |

| Material Composition | Mostly local soil, clay, sand, gravel. Limited use of stabilizers like straw or animal blood. | Engineered soil mix often including a specific ratio of sand, silt, and clay. Use of stabilizers like cement or lime. |

| Formwork | Simple wooden forms. Reused materials, often not uniform. | Engineered, reusable formwork systems. Precise, modular, allowing for greater design flexibility. |

| Compaction | Manual tools like hand rams or simple mechanical tools. Labor-intensive and time-consuming. | Pneumatic or hydraulic rammers. Uniform compaction, faster, less labor-intensive. |

| Wall Thickness & Height | Limited by manual labor capabilities. Typically, lower walls and greater thickness for stability. | Ability to build higher walls with varied thickness due to better support from formwork and improved material strength. |

| Moisture Control | Natural drying, dependent on weather conditions. Limited control over drying process | Controlled moisture content during mixing. Use of additives to manage drying rates and reduce shrinkage. |

| Insulation | Limited insulation properties. Often combined with other materials for thermal regulation | Integration of insulation layers within or on the walls. Improved understanding of thermal mass benefits. |

| Durability and Strength | Dependent on local soil quality and craftsmanship. Varied durability and strength. | Improved durability and strength through engineering and material science. Consistent quality control. |

| Design Flexibility | Mostly straight walls and simple structures. Limited by formwork and material behavior. | Complex geometries, curved walls, and architectural detailing. Computer-aided design (CAD) integration. |

| Sustainability | Inherently eco-friendly due to local materials and low energy use. Limited recycling of materials | Emphasis on low carbon footprint and sustainability. Use of recycled materials and focus on lifecycle assessment. |

| Cost and Accessibility | Low cost due to local materials and labor. Common in rural areas, less so in urban settings. | Variable cost: can be higher due to technology but offset by labor savings. Growing accessibility in both urban and rural areas |

| Quality Control & Consistency | Dependent on skill of laborers and variability of materials. Less predictable outcomes. | Standardized methods and testing. Greater consistency and predictability in outcomes |

| Building Codes & Regulations | Often informal, not subject to modern building codes. Traditional methods passed down through generations | Compliance with modern building codes and standards. Engineering assessments for safety and performance. |

1. Eco-Friendly Material Usage: Rammed earth construction primarily utilizes natural soil, a readily available and minimally processed resource. This approach significantly reduces the environmental footprint, especially when compared to traditional building materials that demand extensive energy for their production and transport (Zhang et al. 2022).

2. Thermal Efficiency: The substantial thermal mass of rammed earth allows it to absorb heat during daylight and release it during cooler hours. This natural temperature regulation leads to considerable energy conservation and enhances indoor comfort, reducing reliance on artificial heating and cooling systems (Zhang et al. 2022).

3. Longevity: Rammed earth is renowned for its durability. With appropriate construction and maintenance, these structures can endure for hundreds of years, as demonstrated by ancient edifices that remain intact (Dabaieh and Sakr 2014).

4. Sustainability in Lifecycle: At the end of their lifespan, rammed earth materials can be repurposed, thereby minimizing waste and reducing the demand for fresh resources. This recyclability plays a crucial role in promoting a circular economy and sustainable practices (Taghiloha 2013).

5. Cultural and Visual Appeal: Rammed earth offers a distinctive aesthetic charm and allows for the creation of structures that blend seamlessly with their environment. It also holds cultural importance in various regions, helping to preserve traditional construction methods (Zhang et al. 2022).

6. Health Advantages: Walls made of rammed earth are permeable, enhancing indoor air quality. Additionally, unlike many manufactured building materials, they do not emit volatile organic compounds (VOCs), contributing to a healthier living environment (Oyawa, Manette, and Musiomi 2015).

7. Economic Benefits: Although initial costs can sometimes be higher, the long-term savings in energy and maintenance make rammed earth an economically viable option. In areas where soil is plentiful, this building method can be particularly cost-effective (Dabaieh and Sakr 2014).

8. Innovation and Flexibility: Ongoing research in rammed earth technology is continually enhancing its performance and versatility. For instance, the incorporation of recycled aggregates into rammed earth can boost its sustainability and decrease waste (Taghiloha 2013).

9. Earthquake Resilience: Properly designed rammed earth structures can exhibit effective seismic performance in earthquake-prone regions, thanks to their mass and the inherent flexibility of the building technique (Dabaieh and Sakr 2014).

Challenges and Limitation

1.Moisture Sensitivity: The moisture content of rammed earth can significantly affect its compressive strength, with optimal strength achieved at specific moisture levels. High or low moisture content can lead to reduced strength, affecting the material’s performance. (Alsudays, Alawad, and Elkholy 2022)

2. Durability Concerns: The durability of rammed earth, particularly in relation to water action, is a significant issue that needs to be addressed to ensure the long-term stability of structures. (Taghiloha 2013).

3.Transdisciplinary Knowledge and Practice: While rammed earth is an economical and desirable building technique, its contemporary practice requires transdisciplinary knowledge and participatory approaches to ensure its sustainable and efficient application (Dabaieh and Sakr 2014).

4.Innovative Development: Incorporating recycled aggregates into rammed earth can enhance its sustainability, but further research and development are needed to optimize the use of these materials and improve the overall performance of rammed earth structures (Taghiloha 2013).

Conclusion

Rammed earth construction has come full circle, reinventing itself from ancient origins to a futuristic vision of sustainable architecture. The two case studies presented reveal thoughtful mergers of vernacular construction wisdom with technological enhancements in structural resilience, thermal modulation, material optimization and quality control.

The Terra Centre sets an example for contextual rural development by skillfully integrating local resources and passive environmental design with targeted improvements in rammed earth technique. The Nk’Mip Desert Cultural Centre stretches the envelope of what rammed earth can achieve through clever modulation of wall thickness and insulation. These projects testify to the green building credentials and aesthetic potential of rammed earth in the 21st century.

When we peel back the layers of history and analyze strides over time, rammed earth has quietly positioned itself at the leading edge of sustainable construction. Its attributes of high compressive strength, thermal mass, breathability, durability, and harmony with nature underpin its value proposition. Standardization of mixed design and construction practices can further unlock its mainstream viability. However, work is still needed to refine moisture control mechanisms, enhance water resistance, develop integrated solutions, and facilitate understanding across disciplines before widespread adoption. If nurtured appropriately through research and policy support, this ancient soil-based technique could well emerge as the building block for a sustainable future.

8 References

Alsudays, Omar M., Omar M. Alawad, and Sherif M. Elkholy. 2022. “Effect of Moisture Content on the Compressive Strength of a Local Rammed Earth Construction Material.” International Journal of Structural and Civil Engineering Research, 10–13. https://doi.org/10.18178/IJSCER.11.1.10-13.

Dabaieh, M., and M. Sakr. 2014. “Transdisciplinarity in Rammed Earth Construction for Contemporary Practice.” Earthen Architecture: Past, Present and Future – Proceedings of the International Conference on Vernacular Heritage, Sustainability and Earthen Architecture, 107–13. https://doi.org/10.1201/B17392-20.

Goh, C. S., M. Gupta, A. E.W. Jarfors, M. J. Tan, and J. Wei. 2010. “Magnesium and Aluminium Carbon Nanotube Composites.” Key Engineering Materials 425: 245–61. https://doi.org/10.4028/WWW.SCIENTIFIC.NET.

Jaquin, Paul. 2011. “A History of Rammed Earth in Asia.” Proceedings of International Workshop on Rammed Earth Materials and Sustainable Structures & Hakka Tulou Forum 2011: Structures of Sustainability.

Losini, Alessia Emanuela, Monika Woloszyn, Taini Chitimbo, Antoine Pelé-Peltier, Sahbi Ouertani, Romain Rémond, Maxime Doya, et al. 2023. “Extended Hygrothermal Characterization of Unstabilized Rammed Earth for Modern Construction.” Construction and Building Materials 409 (December): 133904. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CONBUILDMAT.2023.133904.

Lu, Xiang Ting, and Yuan Ping Liu. 2013. “Rammed Earth Construction: A Sustainable Architecture.” Applied Mechanics and Materials 405–408: 3131–35. https://doi.org/10.4028/WWW.SCIENTIFIC.NET/AMM.405-408.3131.

Oyawa, Walter O., Njike Manette, and Timothy Musiomi. 2015. “Development of a Two-Storey Model Eco-House from Rammed Earth,” October, 1609–18. https://doi.org/10.14264/UQL.2016.802.

Serrano, Susana, Alvaro de Gracia, and Luisa F. Cabeza. 2016. “Adaptation of Rammed Earth to Modern Construction Systems: Comparative Study of Thermal Behavior under Summer Conditions.” Applied Energy 175 (August): 180–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APENERGY.2016.05.010.

Soriano, L. García, C. Mileto, F. Vegas López-Manzanares, and S. García Saez. 2012. “Restoration of Monumental Rammed Earth Buildings in Spain between 1980 and 2011 According to the Archives of the IPCE.” Rammed Earth Conservation, 339–44. https://doi.org/10.1201/b15164-60.

Taghiloha, Ladan. 2013. “Using Rammed Earth Mixed with Recycled Aggregate as a Construction Material.”

Wan, Li, Edward Ng, Xiaoxue Liu, Lai Zhou, Fang Tian, and Xinan Chi. 2022. “Innovative Rammed Earth Construction Approach to Sustainable Rural Development in Southwest China.” Sustainability (Switzerland) 14 (24). https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416461.

Zhang, Fupeng, Lei Shi, Simian Liu, Jiaqi Shi, and Yong Yu. 2022. “Sustainable Renovation and Assessment of Existing Aging Rammed Earth Dwellings in Hunan, China.” Sustainability 14 (11). https://doi.org/10.3390/SU14116748.